Table of Contents | Article doi: 10.17742/ IMAGE.PM.13.1.6 | PDF

Excavating CBC’s Docudrama The Tar Sands

On September 12, 1977, after seven months of internal debate and multiple scheduling delays, CBC aired its 58-minute docudrama The Tar Sands to an eagerly awaiting nation-wide audience of 1.1 million Canadians. Inspired by the academic book The Tar Sands (1976) by University of Alberta political scientist Larry Pratt, CBC’s loose adaptation presented a dramatized re-enactment of the political struggles surrounding Alberta’s then Premier, Peter Lougheed, in negotiating and securing the Syncrude Canada Ltd. agreement to develop Alberta’s Athabasca bitumen sands. The docudrama, which combined actors playing real-life figures with composite characters, was part of CBC’s For the Record series, a collection of what CBC labelled “journalistic dramas” with an objective of “making complex news stories and political issues accessible to a mass audience” (Martin 60). For The Record promotional material described The Tar Sands as:

“Explosive, political drama, zeroing in on powerbroke-ing [sic] by the international petroleum industry. The dramatic story of negotiations and confrontations between major oil industries and the governments of Canada, Alberta and Ontario, that climax with the Canadian taxpayer putting up nearly two billion dollars to ensure development of the Athabasca Tar Sands. Provocative, contemporary drama!”

Explosive and provocative it was. Less than twenty-four hours after the show aired an indignant Peter Lougheed held court in his Edmonton legislature office to a throng of eagerly awaiting journalists where he disclosed his intention to sue the CBC for defamation. The Premier’s pronouncement made national news. It also marked the start of a nearly five-year legal battle. Lougheed originally launched a $2.75 million lawsuit (equivalent to $11.6 million in 2021), which ended in May 1982 in an out-of-court settlement, with CBC paying the Premier $50,000 in damages and $32,500 in costs (respectively $128,000 and $83,400 in 2021). CBC also agreed to televise a nationwide apology and never again “publish” The Tar Sands docudrama.

The settlement helped to bury the docudrama deep in public memory, as it was removed from CBC’s internal archive and made unavailable to staff, and remains so to this day.1 Yet the show’s 1977 broadcast and Lougheed’s ensuing lawsuit and public controversy stands as a critical, though mostly forgotten, moment in the mediated history of Canada’s bitumen sands.2 Indeed, it is only recently that scholars such as Longley (2021) have begun critiquing Lougheed’s legacy and—much like Pratt (1976)—questioning the corner Lougheed and his government backed themselves into. Excavating The Tar Sands affords a unique opportunity to further expose fossil fuel’s long-standing dominant position in the Canadian political and social imagination. This article, as part of a larger research project, is an initial attempt to extract The Tar Sands and its surrounding controversy from the tarry memory hole into which it was cast. It argues that while CBC’s docudrama sought to dramatize and elevate Pratt’s (1976) political critiques, Lougheed’s litigious reaction quickly buried them, obfuscating the real possibility that The Tar Sands—while a work of fiction—portrays the genesis of Alberta’s corporate capture by foreign oil interests.3

Seeing The Tar Sands: Looking Back, Looking Forward

Scholars Debra Davidson and Mike Gismondi have traced the evolution of the tar sands’ visual conventions, which tell a story of taming rugged frontiers, conquest, as well as scientific and technological innovation (Davison and Gismondi 2011; Gismondi and Davidson 2012). The authors conclude their Imaginations article with an analysis of the Great Canadian Oil Sands Company (GCOS, now Suncor) and the “legitimacy work” of images showcasing the immense machinery—from draglines to bucketwheels—involved in mining bitumen. Such images, they argue, “became selling features to the public, symbolizing the enormity of challenges overcome” (Gismondi and Davidson 2012). Author Chris Turner, in his well-researched history of Alberta’s oil patch, identifies the start of what he calls the “High Modern” era as GCOS’s 1967 bitumen plant opening ceremony (Turner 24). What Turner labels the beginning of oil’s “High Modern” period also represents the thickening of petroculture marked by a steady rise in global oil consumption, growing Western efforts to develop domestic synthetic plays, and the further material and cultural enmeshing of oil in everyday life (Wilson, Carlson, and Szeman 2017). And while Stephanie LeMenager (2014) rightly traces back the genesis of oil-driven consumer culture decades earlier, the late 1960s and early 1970s were a period of significant social, economic, and political change for Alberta and its tar sands (Chastko 2004; Elton and Goddard 1979).

Ultimately, what Gismondi and Davidson map is not just the tar sands’ construction, but the construction of its myth; a myth created, in part, from images which remain in public circulation—from advertisements and books to museum exhibitions and education centres—which represent and reconstruct the tar sands’ past. Cultural myths, Roland Barthes reminds us, make history seem natural, yet their creation “is constituted by the loss of the historical quality of things: in it, things lose the memory that they once were made of” (1972, 142). Myths are the selective representations of history sedimented into unquestioned fact. Myths are anchored in ideology and rest upon silences and absences. As Michel-Rolph Trouillot in Silencing the Past suggests, silences occur at “the moment of fact creation (the making of archives); the moment of fact retrieval (the making of narrative); the moment of retrospective significance (the making of history in the final instance)” (1995, 26). The task at present is to bring back into focus one such absence from the hegemonic myth of Alberta’s bitumen sands: CBC’s docudrama The Tar Sands. Acknowledging this “silence”—and the political implications behind it—affords an opportunity to unsettle the sediment of history by revisiting the docudrama and its accompanying controversy and questioning the political forces and driving ideology underwriting its erasure. As such, while scholarship on Canadian oil films traditionally focuses on textual analysis, this article focuses on the show’s broadcast as an inflection point in the myth of the tar sands.

Traces of The Tar Sands

History sediments in books, and while there is mention of The Tar Sands, references are sporadic, disjointed, and often made in passing. For example, the docudrama lands just two sentences in Peter Foster’s 1980 The Blue-Eyed Sheiks noting, “The CBC subsequently produced a ‘docudrama’ based on the Syncrude crisis. Lougheed subsequently sued the CBC for a total of $2.75 million” (99). Meanwhile, Syncrude’s self-published book Syncrude Story: In our own words briefly acknowledges the program (but not the broadcaster) noting: “While [Syncrude President] Frank Spragins was amused to find his name misspelled and pronounced incorrectly in the television show, then Premier Peter Lougheed did not find his portrayal a laughing matter. He launched a $2.75 million lawsuit against the offending station for defamation of character” (1990, 51). Paul Eichhorn, in an essay on the history of CBC’s For The Record series, gives a succinct nod to The Tar Sands and writes that Welsh’s portrayal was “widely known to be an unflattering portrait of Peter Lougheed” (1998, 40). More recently Peter McKenzie-Brown notes that while Larry Pratt’s book was “certainly a reasonable study. However, the docudrama was not. It went beyond the facts to portray the personalities involved—including Frank Spragins and Peter Lougheed—as foul-mouthed, cigar-chomping and conniving” (2017, 145). While these characterizations certainly align with how Lougheed viewed the docudrama, they clash with other interpretations in the historical record.

Perhaps the most detailed documentation of The Tar Sands comes from film scholar Seth Feldman, whose publications (1978, 1986, 1987) and CBC Ideas episode (Feldman 1982) skillfully explore the history, tensions, and politics of the docudrama genre. Feldman viewed Lougheed’s portrayal by actor Kenneth Welsh as “entirely sympathetic” (1978, 73), and some years later reflected, “The Tar Sands was, if not tame, a fairly straightforward production […] There was nothing flamboyant about Kenneth Welsh’s performance […] Pearson’s style was similarly professional and well to the right of glitz” (Feldman 1987, 16). Beyond Feldman, most academic references to The Tar Sands are in passing. It has been briefly mentioned in studies of CBC programming and policies (Miller 1987; MacDonald 2019). Epp (1984), in his analysis of Lougheed’s media strategy, described The Tar Sands as a docudrama “based loosely on a book by Larry Pratt—which portrayed Lougheed as a foul-mouthed dupe of the oil companies during the Syncrude negotiations” (53). David Hogarth’s (2002) study of documentary television in Canada affords The Tar Sands a mid-sentence reference in parentheses. The show has also received some brief attention from scholars studying the relationship between Alberta and its energy industry such as Geo Takach (2017) who succinctly pinpoints The Tar Sands as a seminal moment in the mediated history of Alberta’s bitumen sands. Meanwhile, Debra Davidson and Mike Gismondi (2011) dedicate a paragraph to the show and include an acknowledgment of the program’s erasure from CBC archives. These published and conflicting accounts, together with other fragments such as news clippings and government and institutional archival records, construct The Tar Sands’ current legacy; a legacy—to use a phrase from Michel-Rolph Trouillot—built on a “silence” (Trouillot 1995).

Myth and Rediscovery of The Tar Sands

In 1977, when CBC aired The Tar Sands, Imperial Oil—a Canadian oil company controlled by Exxon and portrayed in The Tar Sands—was intensifying its oil sands play in Cold Lake, Alberta. Meanwhile, Exxon’s Dr. James Black, Scientific Advisor in the Products Research Division of Exxon Research & Engineering, had already told company management that summer “that the most likely manner in which mankind is influencing the global climate is through carbon dioxide release from the burning of fossil fuels” (Hall 2015). Yet broad public awareness as to the link between burning fossil fuels and climate change would not happen for more than a decade. The now universal scientific consensus of anthropogenic climate change and its explicit link with burning fossil fuels has an undeniable impact upon our relationship with media texts about petroleum and its attendant socio-political and economic structures. In the case of The Tar Sands, its rediscovery in the context of this article and my wider research project allows us to consider how the docudrama—and the energetic political reaction which lead to its quashing—make visible the power and grip of “petro-hegemony” in Alberta both in the 1970s and today. Drawing from Theo Lequesne (2019), petro-hegemony is the public internalisation of a Gramscian common sense and philosophy rooted in three relations of power—consent, coercion, and compliance—which, together, serve to further fossil fuel companies’ material and discursive objectives. Of particular interest for the case at hand is Alberta’s political and cultural climate whereby critics who dare question the power and reach of foreign-owned oil companies are silenced, marginalized, and/or vilified. Also relevant is the province’s economic reliance upon the foreign-dominated fossil fuel industry which forces compliance through a structured dependency and addiction thus serving to maintain hegemony.

Understanding the reaction to The Tar Sands requires us to first consider Alberta’s dominant ideology and the myth surrounding Lougheed. R. W. Wright (1984) suggests that Alberta has come to operate primarily under a “hybrid” corporatist ideology of “managerial capitalism,” a perspective which is “entrenched and virtually unopposed” in the province (105). Related, and almost three decades later, Davidson and Gismondi (2011) suggest:

“In many ways, it was ideology, not economics, which ensured the tar sands’ eventual development. A westernized worldview of frontier individualism, a utilitarian view of ecosystems, and confidence in continued progress supported decades of investment in research and marketing by the provincial state, public investments that were crucial to eventually attracting the interest of private capital.” (170)

Thus, it was Conservative ideology—under Lougheed’s Premiership—which ensured the tar sands were developed and never nationalized (Doern and Toner 35; Pratt 1976). Lougheed’s Conservatism was grounded on a commitment to extract the maximum benefit out of the provinces’ natural resources for its people by private industry. Steward summarises Lougheed’s approach as follows:

“Lougheed saw government as a counterweight to the economic power and influence of the petroleum industry. He believed that since government managed natural resources on behalf of Albertans it had a responsibility to obtain as much revenue and other benefits as possible from those resources.” (1)

Kevin Taft (2017), in his stinging critique of oil’s “deep state” presence in Alberta, eulogises Lougheed as a Premier who fiercely fought for Alberta’s interests and would bend the knee to no one. This portrayal is particularly noteworthy as Taft’s book advances a “deep state” thesis that Alberta government has since been captured by the oil industry and an assemblage of interested political and bureaucratic boosters. However, for Taft, Lougheed’s government was unmolested by corporate or political pressures which swayed subsequent Premiers. Taft’s divine framing of Lougheed is consistent with his mythic position in Alberta lore as “King Peter” (Lewis 27) of Camelot West. It is then perhaps understandable why The Tar Sands—both Pratt’s and CBC’s version—was viewed within Alberta as an act of lèse-majesté.

Lougheed’s mythic status rests, at least partly, on the erasure of The Tar Sands from public memory. The CBC’s docudrama directly challenged the doubly articulated myths of Syncrude’s founding and Lougheed’s Premiership. To this end, The Tar Sands presents a dramatized interpretation of events depicting a proud and determined Premier Lougheed becoming boxed in over the course of the Syncrude negotiations by world events and pressure applied by the foreign-controlled Syncrude consortium. Here, it is perhaps prudent to offer more information on the TV show itself, beginning with the show’s two-minute disclaimer, aired at the start and read by journalist and CBC icon Barbara Frum. The disclaimer informs the audience that The Tar Sands is, “a work of fiction constructed around certain known events” based on “an imagined recreation of negotiations leading up to an agreement reached on February 3, 1975” (Feldman 1978, 71). “Since most of the agreement was worked out behind closed doors,” Frum tells viewers: “Much of the film’s dialogue and many of its scenes and characters are, of necessity, fiction” (ibid).

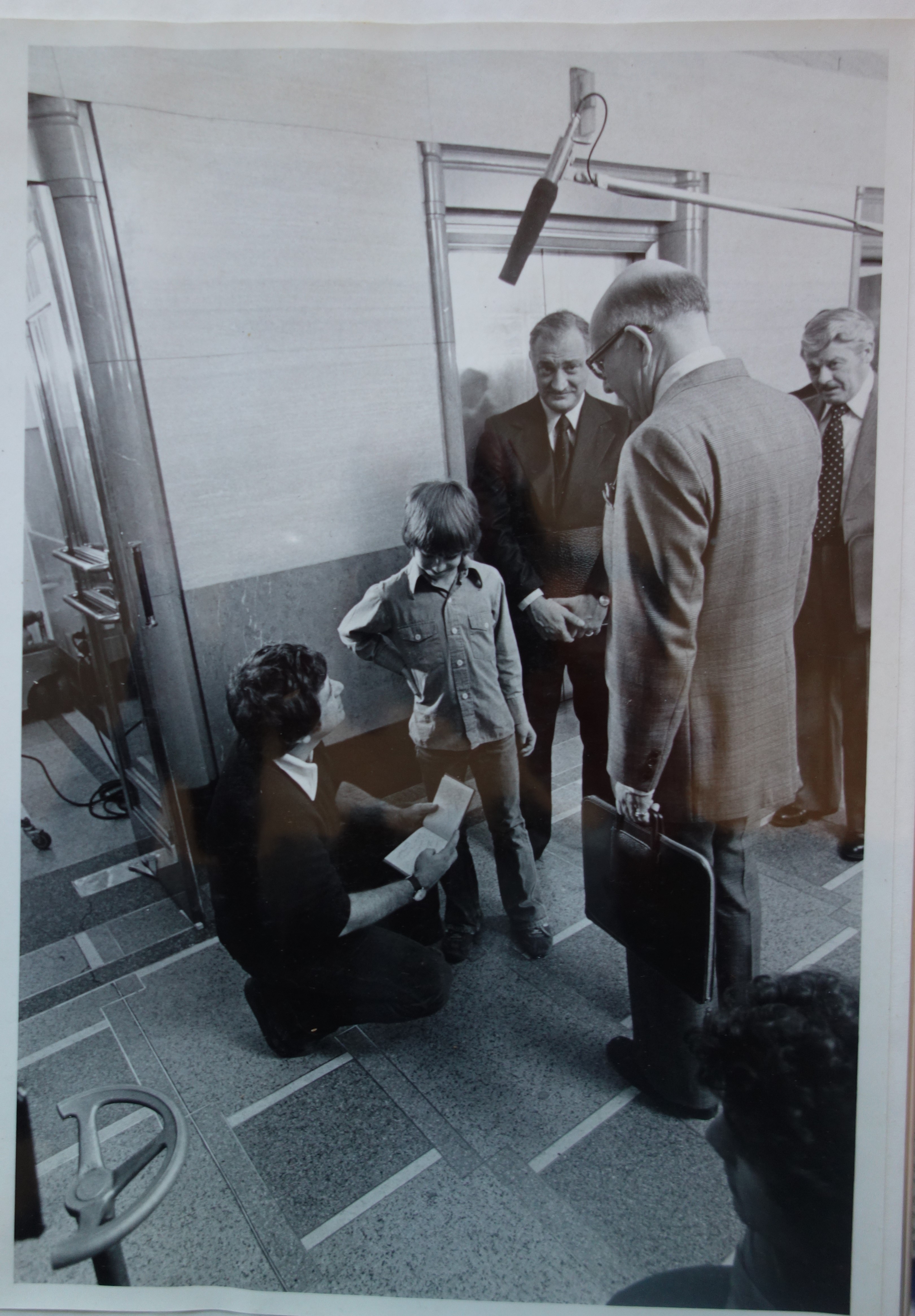

Frum also briefly discusses the show’s four main characters, differentiating between two characters with real-world counterparts and two composite characters. The two real-world characters were the show’s lead, Premier Peter Lougheed, expertly portrayed by Canadian actor Kenneth Welsh and, second, Frank Spragins, President of Syncrude Canada (Mavor Moore) who is portrayed as the spokesperson and chief negotiator for Syncrude’s interests (Figure 4). The Tar Sands also featured two main composite characters, the most prominent of which was Willard Alexander (Ken Pogue). Alexander was a perpetually critical, cigarette-smoking, alcohol-drinking confidant of Premier Lougheed whose function was to represent “the Alberta civil servants who argued against proceeding with the Athabasca tar sands development in the manner finally chosen” (Pearson, 1977). The second main composite character was the sleek and smartly dressed David Bromley, played by George Touliatos (Figure 4). In the disclaimer Frum identifies Bromley as an “oil company representative” who is “a composite of the many oil men involved in the real negotiations,” however he is identified in the show itself as being from Imperial Oil (Pearson, 1977). Bromley, with his disdainful and impatient attitude towards public service and relentless focus on profit, perfectly personifies Pratt’s (1976) critical view of foreign interest squeezing the Albertan and Canadian government to their advantage.

The “real life” characters in The Tar Sands are also caricatures. Both the on-screen Lougheed and Spragins are dramatic representations of the interpretation of certain historical events based on Pratt’s book and supplemental research conducted by the show’s two main writers, Peter Pearson and Ralph Thomas. As will be discussed in the next section, Premier Lougheed took exception to his portrayal and that of the Syncrude negotiations. However, there were also public misgivings about Frank Spragins’ representation. For some in the industry such as John Barr, Head of Syncrude’s Public Relations department, and Harold Millican, former Lougheed Chief of Staff and prominent oilman, Spragins was a “gentleman” and Moore’s portrayal was unfair. Calgary-based petroleum industry historian Peter McKenzie Brown summed up the on-screen Frank Spragins as a “foul mouthed […] cigar chomping, American oilman” (Spragins 2012, 22). In a 2012 interview conducted by McKenzie Brown for The Oil Sands Oral History Project, Nell Spragins described her husband Frank’s portrayal as, “unbelievable, you know. Just how they could make it up like that and not even try to come close to what kind of man he was, unbelievable, really” (ibid). Yet compared to Imperial Oil’s fictional representative David Bromley, Frank Spragins’ screen persona was not unlikeable. Larry Pratt, who was not involved in making CBC’s adaptation of his book, said in a September 13, 1977 Canada-wide live radio interview on CBC Morning Side: “I didn’t think that the portrayal of Mr. Spragins was that unfair. But it is the case that they had to personify—they had to personify the oil industry in one individual and, if it’s unfair to Mr. Spragins, that’s unfortunate” (CBC Morning Side, 1977).

Frank Spragins appears for the first time in The Tar Sands about four minutes into the broadcast when “top executives” from the American-controlled oil companies behind Syncrude Canada Ltd. have been asked to meet with Premier Lougheed (Welsh). The scene takes place in a screening room where Premier Lougheed is about to be shown a Syncrude advertisement intended to help sell the infrastructure project to Canadians. As this scene unfolds the show’s narrator—famed NFB director and producer Donald Brittain—provides context for the gathering and introduces the audience to the “American-controlled” oil companies in the room and “Syncrude’s President Frank Spragins, a Mississippian by birth and in his words, ‘A Canadian by choice’” (Pearson, 1977). Spragins, portrayed by celebrated actor Mavor Moore, delivers his tar sands pitch in an exaggerated raspy rounded southern drawl which serves as a persistent reminder of Spragins’ foreign origin and presumed foreign allegiance.

Frank Spragins never officially commented on the CBC broadcast, however Syncrude’s head of Public Relations John Barr spoke to the media. Barr defended Lougheed’s bargaining skills, called the show “inaccurate,” and said The Tar Sands “is best treated as a work of imagination, or, better, as a work of fantasy” (Calgary Herald, 1977). As for why Syncrude did not react to The Tar Sands in an official capacity, Barr said Syncrude “decided not to make any comment […] It would be like trying to refute Mein Kampf —you wouldn’t know where to start” (ibid). While Syncrude didn’t know where to start, Premier Lougheed did: by calling his lawyer.

Defamation and the Drama of Docudrama

As Peter Lougheed publicly expressed his displeasure about The Tar Sands during a news conference the morning after its September 12th broadcast, the wheels were already in motion for a defamation lawsuit. Lougheed’s lawyers had sent a preemptive telex to CBC on September 11, 1977 warning of possible legal action and then followed up two days later with a hand-delivered registered letter sent to CBC Edmonton requesting “the name and address of the operator of your station” (CBC ATIP A0062824_1-000759). Although the letter was delivered to CBC Edmonton, the Premier’s real target was further east: the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s national headquarters in Toronto, Ontario.

The Tar Sands had been delayed multiple times since its first anticipated air date in February 1977 due to CBC management concerns. The Barbara Frum disclaimer was added in what Feldman, post-broadcast, called “a futile attempt to avoid legal repercussions” (1978, 72). Nonetheless, the disclaimer helped the program get to air. But, publicly, the specifics of The Tar Sands’ path to being broadcast by the CBC were kept a mystery. Indeed, even one of CBC’s top brass seemed surprised about the show’s airing as reported in The Calgary Herald: John Hirsch, head of CBC-TV drama, told reporters and critics who saw a preview of the work Wednesday that God alone knows “who let it go on the air” (Nelson 1977, C3). Publicly, the CBC was confident about The Tar Sands with producer Ralph Thomas quoted at the pre-screening as saying “no legal complications are expected” (Zanger 1977, 26). However, Mel Hurtig, staunch Canadian nationalist and publisher of Larry Pratt’s The Tar Sands, thought differently. When Hurtig was asked how he thought Lougheed and Spragins would react to the show, he replied “I suspect both of them are going to go through the roof” (Waters 1977, A23). Perhaps unsurprisingly, with his political leanings, Hurtig stood behind the show, commenting “It is a very accurate reflection of the process of bargaining that occurred over the Syncrude plant” (Calgary Herald 1977, A1) and went as far to say that the CBC had “performed a remarkable public service and has, in fact, been very courageous. It (the show) was unique, one of a kind. They’ll never put on anything as tough” (Toronto Star 1977, A69).

Hurtig, it should be noted, also had a cameo in The Tar Sands. The brief scene shows Hurtig re-enacting a 1973 news conference where he revealed a leaked civil service report to the press. The report—which plays a vital role in Pratt’s 1976 book—was authored by a collection of top Alberta government senior civil servants and took a critical position towards what it described as the creep of foreign ownership of the province’s tar sands (Pratt 1976, 22; also see Longley 2021). Hurtig was supposedly given the confidential report—titled “The Fort McMurray Tar Sands Strategy”—by an unnamed civil servant who had become frustrated with the Lougheed government for ignoring the report’s recommendations (ibid).

Hurtig was correct: Lougheed went through the roof. Visibly angry at a September 13th press conference, Lougheed used a prepared statement to describe The Tar Sands as “immoral,” “outrageous,” and “unfair,” commenting:

“If the CBC is allowed to get away without a fight with this approach of characterisation of real people involved in public events in the guise of a drama to suit the CBC’s interpretation of such events then, they no doubt will not hesitate to use this vehicle to escalate their distortions of public affairs and in so doing, to destroy or damage reputations.” (Albertan Edmonton Bureau 1977, A33)

Members of Lougheed’s cabinet were equally disturbed by The Tar Sands. Lougheed’s Business Development Minister Bob Dowling said, “It was a bunch of garbage […] The writer has no regard for 5,000 people who have jobs up there (on the Syncrude project)” (Gilchrist 1977, A1). Alberta’s Solicitor-General Roy Farran told the Edmonton Journal the program was “a complete distortion of fact,” and went on to make flippant comparisons with Nazi propaganda commenting, “I think it was similar to Dr. Goebbels at his worst” (Hume 1977, P1). Minister of the Environment Dave Russel was more concise, simply calling it “a load of crap” (ITV News 1977). While there was Conservative consensus about the program, NDP leader Grant Notley believed Lougheed overreacted to the broadcast saying, “Quite simply if one reads the Syncrude papers that is the story that was there” (Thorne 1977, A6).

The docudrama’s national broadcast was an act of counter-hegemony; it openly challenged the near sedimented view of the Syncrude negotiations as a public win, not a corporate oil coup. Consistent with Pratt’s (1976) book, The Tar Sands offered a dramatized interpretation critical of the sway and power of foreign corporate oil interests in Canada. However, as argued above, this dissenting perspective was discursively dismissed by ruling politicians and coercively quashed via the court system. Together these actions worked towards achieving hegemony over Syncrude’s founding and the presence and implications of foreign oil corporations in the tar sands. Nonetheless, and as Feldman notes, the fact that CBC made a docudrama about Alberta’s “tar sands” was a testament to its standing and the accompanying politics it had attained. Feldman (1985) suggests:

“The act of seeing the recreation after being taught the history, reading the news or living through the period is essentially narcissistic; we are looking at something that is already part of ourselves. Further satisfaction is derived from the communal sharing of an event and the mass catharsis inherent in jointly exposing social anxieties experiencing the retelling of a familiar horror.” (349)

If, as Feldman argues, watching a docudrama is a “narcissistic” experience, for Lougheed it was likely closer to “narcissistic mortification” (Eidelberg 1957). A clinical term popularised by psychiatry professor Ludwig Eidelberg in the late 1950s, narcissistic mortification refers to feelings of anger and terror over the loss of control over a situation. “If the unpleasure caused by a narcissistic mortification is too great,” Eidelberg warns, “the individual eliminates it from his consciousness by repression or denial” (1957, 596). While it is not possible to know how Lougheed’s consciousness handled The Tar Sands, Lougheed certainly ensured it was repressed from the Canadian consciousness.

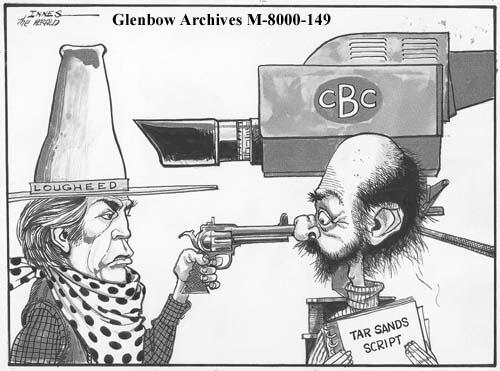

Lougheed’s actions in the media and courts are consistent with his overall media strategy as premier, which was characterised by image control and party-wide message discipline (Epp 1984). Yet not only was the CBC docudrama firmly outside of Lougheed’s command, its dramatized depiction of events—shown to a nation-wide audience—directly disputed Lougheed’s own carefully constructed media image. As one of Canada’s first media savvy politicians, a case could be made that Lougheed had little choice but to sue the CBC; performative politics demanded it. Marshall McLuhan once said of Peter Lougheed, “on TV Lougheed strives for a role rather than a goal” (Hustak 1979, 191). In this case, Lougheed’s role was one of an indignant western Premier eager for justice (and keen to be seen seeking it) after being slighted one too many times by feckless Easterners.

At the time, those seen criticizing the province’s Conservative establishment were largely treated with contempt as Pratt himself acknowledges in The Tar Sands: “The present political atmosphere in Alberta is such that criticism tends to be regarded as treasonous (‘alien forces,’ to quote Premier Lougheed) and unpleasant facts are dismissed as ideological heresy” (1976, 10). Pratt’s quotation is significant as it acknowledges the inhospitable political environment for narratives which sought to challenge the dominant government discourse. As an economic nationalist, Pratt sought to caution against the growing powers and political sway of foreign-owned oil corporations whose interests, from his perspective, didn’t necessarily align with the province. However, Pratt’s concerns were dismissed and shelved while his presence was met with hostility; the CBC docudrama based on Pratt’s book would meet the same fate.

Immediately after the show aired, Lougheed, his cabinet, and indeed most critics directed their criticism towards The Tar Sands docudrama format, describing it as “unfair” and “unjust”; as a medium to explore contemporary politics it was decried as heretical. Yet as Feldman rightly notes, “the images that result from both The Tar Sands and The National are simply two interpretations of the same role, a role that may loosely be described as “the public image of Peter Lougheed” (Feldman 1978, 72). Both representations—The Tar Sands and The National—are synthetic, processed for public consumption. Interestingly, Lougheed and his cabinet reacted primarily to the medium and not the message, thus directing public attention towards the dramatization of current events and not the critiques it contained. To be sure, the docudrama format could have easily been deployed as a mediated mistrial to memorialize the conquests of King Peter of Camelot West. Yet the majority of public discourse around The Tar Sands—including news articles—centred on the ethics and use of docudrama to explore the Syncrude Agreement. Consequently, discussions around the creeping power of foreign oil interests over Alberta’s resources were largely sidelined in favour of debate around the docudrama’s scandalous format and propagandist nature; petro-hegemony prevailed. While the docudrama may have sought to tell a cautionary tale about the potential consequences of foreign oil’s sway over Alberta, Lougheed and his supporters drew upon discursive and legal means to quickly quash this heretical challenge to the dominant orthodoxy.

Conclusion: Repression and Rediscovery

The initiation of a defamation lawsuit against CBC for The Tar Sands sealed the show’s fate as a media event destined to become repressed in the Canadian consciousness. Larry Pratt’s 1976 book, on the other hand, remains publicly available, though it has become increasingly difficult to find despite having sold 13,000 copies (Mackenzie-Brown 2017). Yet The Tar Sands—both Pratt’s book and the banned CBC docudrama—are important texts for their contrapuntal narratives challenging the dominant myths around Syncrude’s founding, concessions won and lost, and the influence of corporate power. Reflecting on Lougheed’s legacy, Foster (1980) suggests:

“It remains uncertain just how much of Alberta’s modern-day wealth can be attributed to Lougheed’s trenchant bargaining stance. The OPEC crisis, by quadrupling oil prices, would have made the province much richer whoever was in power, but his intransigence has led to him being inseparably linked to the province’s fortune. In the eyes of many Albertans, it is Lougheed who has made the province the wealthiest and fastest growing in Canada.” (43)

Forty years later, Foster’s statement would undoubtedly be taken as heretical by many, especially when compared to the legacy of many subsequent Albertan premiers. Moreover, Albertans and Canadians have unquestionably benefited from the tar sands extraction which Lougheed kickstarted. Yet if Taft’s (2017) “deep state” thesis is correct and democratic institutions provincially in Alberta and federally have indeed been “captured” by the oil industry, who let them in and under what terms? Taft, as argued above, puts the blame squarely beyond Lougheed’s premiership. But what if CBC’s docudrama The Tar Sands captures the origin story of the corporatization and exploitation of the Athabasca tar sands?

Ours is a political moment when the tar sands’ future is openly and actively challenged, and so too is the ideological grip of fossil fuels. Despite decades of corporate obfuscation and obstruction, the link between burning fossil fuels and climate change is undeniable. Spurred by an ever-intensifying climate emergency, there is near universal consensus on the need to rapidly transition away from societies and economies built on oil, especially resource intensive oil such as the tar sands; however, some political and corporate actors continue to actively challenge the pace and urgency of this transition in pursuit of their own interests (Carroll 2021). To be clear, neither the docudrama nor Pratt’s book addressed the issue of climate change, while the environmental concerns expressed, though present, were minor. Yet Pratt’s (1976) concerns about the influence of corporate power over government formed the docudrama’s core: concerns about petro-hegemony’s creep. Indeed, while works such as Taft (2017) are rightly critical of Alberta’s current deep state oil links, the reaction to a now forty-four-year-old docudrama reveals concerns early in Alberta’s synthetic energy history as to the consequences of a political culture and common sense underwritten by and intertwined with corporate oil interests.

In conclusion, if docudrama provides the building blocks for “self recognition” (Feldman 1985, 354), Premier Lougheed did not like what he saw, so much so that he had it metaphorically thrown into a tar pit. Common sense at the time—particularly in Alberta—accepted this dogma; the docudrama was heretical. Yet, The Tar Sands was not an indictment of Lougheed, despite him seeing it that way. It was and remains a skillfully dramatic and damning critique of fossil-capitalism; a critique which remains as compelling today as when The Tar Sands aired forty-five years ago, for its first and only time.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by an Insight Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada under Grant 430-2018-1019.

Works Cited

Albertan Edmonton Bureau. “Lougheed’s statement.” Calgary Albertan, 14 Sept. 1977, p. A33.

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. Translated by Annette Lavers, Hill and Wang, 1972.

Calgary Herald. “‘Inaccurate,’ says oilman of TV show on Tar Sands deal.” 13 Sept. 1977, p. A1.

Carroll, William K., editor. Regime of Obstruction: How Corporate Power Blocks Energy Democracy. Athabasca University Press, 2021.

CBC Morning Side. “CBC Morning Side with Don Harron.” Radio interview with Larry Pratt, Harold Millican, and John Barr. 13 Sept. 1977.

Chastko, Paul Anthony. Developing Alberta’s Oil Sands: from Karl Clark to Kyoto. Calgary, University of Calgary Press, 2004.

Davidson, Debra J., and Mike Gismondi. Challenging Legitimacy at the Precipice of Energy Calamity. New York, Springer Science & Business Media, 2011.

Eichhorn, Paul. “For The Record: Watching Canadian Reality.” Take One: Film & Television in Canada, no. 20, June 1998.

Eidelberg, Ludwig. “An Introduction to the Study of Narcissistic Mortification.” The Psychiatric Quarterly, vol. 31, 4 Oct. 1957, pp. 595-597.

Elton, David K., and Arthur M. Goddard. “The Conservative Takeover, 1971–.” Society and Politics in Alberta: Research Papers, edited by C. Caldarola, Methuen, Toronto, 1979, pp. 49-72.

Epp, Robert. “The Lougheed Government and the Media: News Management in the Alberta Political Environment.” Canadian Journal of Communication, vol. 10, no. 2, 1984, pp. 37-65. DOI: doi.org/10.22230/cjc.1983v10n2a338

Feldman, Seth. “O Television Docudrama: The Tar Sands,” Cine-Tracts, 4 Spring-Summer, 1978, pp. 71-76. Retrieved from https://library.brown.edu/cds/cinetracts/CT04.pdf.

Feldman, Seth. “Styles of truth. Part One. Decoding the Documentary: Performance on Trial”. CBC Ideas, CBC Radio. Original airdate: 14 Dec. 1982.

Feldman, Seth. “CBC Docudrama-Since The Tar Sands: What’s New?” Cinema Canada, vol. 142, 1987, pp. 16-17.

Feldman, Seth. “Footnote to Fact: The Docudrama.” Film genre reader, edited by Barry Keith Grant, University of Texas Press, 1986, pp. 344-369.

Gilchrist, Mary. ”Lougheed to Fight CBC in West”, The Calgary Herald, 14 Sept. 1977, p. A1.

Gismondi, Mike, and Debra J. Davidson. “Imagining the Tar Sands 1880-1967 and Beyond.” Imaginations: Journal of Cross-Cultural Image Studies, vol. 3, no. 32, 2012, pp. 68-103. http://dx.doi.org/10.17742/IMAGE.sightoil.3-2.6.

Hall, Shannon. “Exxon Knew About Climate Change Almost 40 Years Ago.” Scientific American, 26 Oct. 2015. Retrieved from: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/exxon-knew-about-climate-change-almost-40-years-ago/.

Hogarth, David. Documentary Television in Canada. Montreal, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002.

Hume, Stephen. “Premier Silent Over TV Drama.” Edmonton Journal, 13 Sept.1977, P.1.

Hustak, Allan. Peter Lougheed: a Biography. Toronto, McClelland and Stewart, 1979.

ITV News. Evening News. ITV News Edmonton, 13 Sept. 1977.

Jekanowski, Rachel Webb. “Fuelling the Nation: Imaginaries of Western Oil in Canadian Nontheatrical Film.” Canadian Journal of Communication, vol. 43, no. 1, 2018, pp. 111-125.

Latour, Bruno. Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1999.

LeMenager, Stephanie. Living Oil: Petroleum Culture in the American Century. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013.

LeQuesne, Theo. “Petro-hegemony and the Matrix of Resistance: What can Standing Rock’s Water Protectors Teach Us About Organizing for Climate Justice in the United States?” Environmental Sociology, vol. 5, no. 2, 2019, pp. 188-206.

Lewis, Robert. “A Show of Power from King Peter.” Maclean’s, 26 Nov. 1979, pp 27-30.

Longley, Hereward. “Conflicting Interests: Development Politics and the Environmental Regulation of the Alberta Oil Sands Industry, 1970–1980.” Environment and History, vol. 27, no.1, 2021, pp. 97-125.

MacDonald, Monica. Recasting History: How CBC Television Has Shaped Canada’s Past. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019.

Martin, Sandra. “Television: Any Resemblance… is Purely Intentional.” Maclean’s, 21 Feb. 1977, pp. 59-60.

McKenzie-Brown, Peter. Bitumen: The People, Performance and Passions Behind Alberta’s Oil Sands. Peter McKenzie-Brown, 2017.

Miller, David, and Claire Harkins. “Corporate Strategy, Corporate Capture: Food and Alcohol Industry Lobbying and Public Health.” Critical Social Policy, vol. 30, no. 4, 2010, pp. 564-589.

Miller, Mary-Jane. Turn Up The Contrast: CBC Television Drama Since 1952. UBC Press, 1987.

Nelson, James. “Controversial Tar Sands Drama Goes Ahead on Monday,” The Calgary Herald, 9 Sept. 1977, p. C3.

Pearson, Peter. “The Tar Sands.” For the Record, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Toronto. 12 Sept. 1977.

Peters, John Durham. The Marvelous Clouds: Towards a Philosophy of Elemental Media. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Pratt, Larry. The Tar Sands. Edmonton, Hurtig, 1976.

Rennie, Bradford James. Alberta Premiers of the Twentieth Century. Regina, Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina, 2005.

Spragins, Nell. Interview by Peter McKenzie-Brown. The Oil Sands Oral History Project, Petroleum History Society, June 7 2012. Retrieved from https://glenbow.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Spragins_Nell.pdf.

Steward, Gillian. “Betting on Bitumen: Alberta’s Energy Policies from Lougheed to Klein.” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, 2017. Retrieved from https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/BC%20Office/2017/06/bettingonbitumen.pdf.

Szeman, Imre. “Crude Aesthetics: The Politics of Oil Documentaries.” Journal of American Studies, vol. 46, no. 2, 2012, pp. 423-439.

Syncrude. Syncrude Story: In Our Own Words. Fort McMurray, Syncrude Canada Ltd., 1990.

Taft, Kevin. Oil’s Deep State: How the Petroleum Industry Undermines Democracy and Stops Action on Global Warming in Alberta, and in Ottawa. Toronto, James Lorimer & Company Ltd., Publishers, 2017.

Takach, Geo. Tar Wars: Oil, Environment and Alberta’s Image. Edmonton, University of Alberta, 2017.

Thorne, Duncan. “Premier Portrayal Correct, says NDP Leader.” Calgary Albertan, 14 Sept. 1977, A6S.

Toronto Star. “Lougheed Portrayed as Sellout on Oil.” Toronto Star, 13 Sept. 1977, A69.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston, Beacon Press, 1995.

Turner, Chris. The Patch: The People, Pipelines, and Politics of the Oil Sands. Toronto, Simon & Schuster, 2017.

Waters, Jim. “Television and Radio by Jim Waters.” Edmonton Journal, 9 Sept. 1977, A23.

Wilson, Sheena, Adam Carlson, and Imre Szeman, editors. Petrocultures: Oil, Politics, Culture. Montreal, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017.

Wright, R. W. “The Irony of Oil: The Alberta Case.” The Making of the Modern West: Western Canada since 1945, edited by A. W. Rasporich, Calgary, University of Calgary Press, 1984, pp. 105-114.

Zanger, Paul. “CBC Oil Drama Surfaces: Tar Sands to be Seen on Monday.” Winnipeg Free Press, 9 Sept. 1977, p. 26.

Image Notes

Figure 1: CBC, For the Record. Pamphlet, 1977. Library and Archives Canada, Peter Pearson Fonds, R-899, VOL 12; File: For the Record “Tar Sands” Correspondence and Memoranda 1976-1978-12-14.

Figure 2: CBC, For the Record. Advertisement, 1977. Source: Peter Pearson, Personal Collection.

Figure 3: Peter Lougheed (Kenneth Welsh) and Willard Alexander (Ken Pogue) in The Tar Sands, 1977. Source: Peter Pearson, Personal Collection. Reproduced with the permission of Peter Pearson.

Figure 4: Production still from The Tar Sands featuring director Peter Pearson (crouching in foreground), Mavor Moore (with glasses and his back to the camera) in character as Frank Spragins, President of Syncrude Canada Ltd., and George Touliatos as oil company representative David Bromley, 1977. Source: Peter Pearson, Personal Collection. Reproduced with the permission of Peter Pearson.

Figure 5: Kenneth Welsh as Peter Lougheed in The Tar Sands, 1977. Source: Peter Pearson, Personal Collection. Reproduced with the permission of Peter Pearson.

Figure 6: “Them’s fightin’ words, Mister.’” (CU12608121) by Tom Innes. Courtesy of Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary. Reproduced with the permission of Glenbow Archives.

Notes

-

The film is not available from CBC, however the author has viewed a copy. This article is based on an ongoing research project that has involved multiple archive visits, government Access to Information and Privacy requests, as well as interviews with individuals involved in making The Tar Sands, reporting on the controversy, and the court case itself. The film’s source cannot be named at present given the nature of the project and effort to locate it.↲

-

While relatively little attention has been given to The Tar Sands, there is an established body of academic research on Canadian films about oil as well as the cultural representation of Alberta’s tar sands including, but not limited to Jekanowski (2018), Szeman (2012) and Takach (2017).↲

-

My use of “capture” draws from Miller and Harkins (2010) who propose “corporate capture” to conceptualise corporations’ ability to obtain and maintain power and self-serving influence across multiple social, political, ideological, and communicative domains. Taft (2017) in his writing also uses the idea of capture to describe the industry’s role and influence in Alberta’s “deep state.”↲